De Latino sine Flexione; Principio de Permanentia

https://www.amazon.de/-/en/Giuseppe-1858-1932-Peano-ebook/dp/B018PL3XUO/ref=sr_1_1?crid=2P18UIZ32264T&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.YTH

4.—Conjugatione de verbo

«Personae verborum possunt esse invariabiles, suffìcit variari ego, tu, ille, etc.».

LEIBNIZ.

Lingua latino habet discurso directo, ut:

”Amicitia Inter malos esse non potest”

et discurso indirecto:

”(Veruni est) amicitiam Inter

malos esse non posse”.

si nos utimur semper de discurso indirecto, in verbo evanescit desinentia de persona, de modo, et saepe de tempore.

Sumimus ergo nomen inflexibile, per persona modo et tempore, sub forma magis simplice, qui es imperativo, activo et passivo. Regula es:

«a) Ad forma

inflexibile “es, pote, vol, fi”

responde infinito “esse, posse, velle, fieri”.

b) Ad forma inflexibile de allo verbo adde -re, et te habe infinito, ut es in vocabulario latino.

c) Ad verbo activo adde -re, et te habe passivo.

d) Nos transforma verbo deponente in activo».

(Verbo ”vol, dice, duce, face”, et regula d) non es exacto latino classico).

Nos indica persona cum ”me, te, nos …”, modo cum ”si, ut, quod, …”, tempore cum ”heri, jam, in passato, nunc, cras, in futuro, vol, debe, …”.

Ex. ”Me scribe.—Vos lege.—Cras me i ad Roma.

—Cras me, postquam veni ad Roma, scribe ad te.

—Heri me lege dum te scribe et antequam Petro veni.

—Si te narra, nos audi.—Ut te vale.”

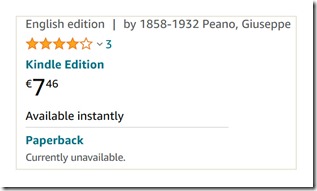

Peano, Giuseppe, 1858-1932. De Latino sine Flexione; Principio de Permanentia. HardPress Publishing. Kindle Edition includes seven chapters.

Peano’s examples translated

|

Latino sine flexione

|

English

|

|

Cras me i ad Roma.

|

Tomorrow I will go to Rome.

|

|

Cras me, postquam veni ad Roma, scribe ad te.

|

Tomorrow, after I have come to Rome, I will write to you.

|

|

Heri me lege dum te scribe et antequam Petro veni.

|

Yesterday I read while you were writing and before Peter came.

|

|

Si te narra, nos audi.

|

If you tell us, we listen.

|

100 exemplo de interlingua 51 – 61

|

|

Latino sine flexione

|

Latina

|

English

|

|

73

|

Te pote frange, non flecte, me.

|

Frangere potes, ne me inflectas.

|

You can break, don’t bend me.

|

|

|

Translating this sentence was challenging because we can read "me" either as "I" or "me." Similarly, "te" can be either a subject or an object. Also, that comma before the last "me" makes the sentence even more vague.

What I wrote above is an excellent example that simplifying language has its limits. My subject is "mi," and my object is "me." The corresponding words for the second person singular are "tu" and "te." Of course, my practice violates the rules of grammar written by Peano.

|

|

74

|

Medico es periculo plus que morbo.

|

Plus est periculi e medico quam a morbo.

|

There is more danger from the doctor than from the disease.

|

|

75

|

Qui designa uno, exclude alio.

|

Designatio unius est exclusio alterius.

|

The designation of one is the exclusion of the other.

|

|

76

|

Quem plure time, debe time plure.

|

Necesse est ut multos timeat quem multi timent.

|

Meaning:

Those who are most frightening must be feared most of all (people).

|

|

77

|

Dic ad me cum qui te i, et me dic qui te es.

|

Dic mihi quis tecum iturus es, et dicam tibi quis sis.

|

Tell me who you are going with, and I will tell you who you are.

|

|

78

|

Nos ne debe disputa de gustu.

|

De gustibus non est disputandum.

|

There is no disputing about tastes.

|

|

79

|

Qui ama me, ama et cane de me.

|

Qui me amat, amat et canem meum.

|

He who loves me loves my dog.

|

|

80

|

Morte pro patria es dulce.

|

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

|

It is sweet and glorious to die for the fatherland.

|

|

81

|

Hodie ad me, cras ad te.

|

Hodie mihi, cras tibi.

|

It is my lot today, yours tomorrow.

|

|

82

|

Nos ne cupe quod ne gno.

|

Nolumus quod nescimus.

|

No desire for the unknown.

|