Blowing in the Wind

An older man laid down on his bed. He suffered from the heat of summer in the old hospital that missed the air-condition. The pavement went just along the side of the wooden house, and voices from the street came indoors to the first floor where the man spent the last moments of his life. This evening was a more restless night than usual because of Midsummer eve.

Now and then, some people stopped under the window and changed news. Nurses went immediately to the window and asked people to leave because they were disturbing the palliative care patients. The older man was alone in the room and didn’t get annoyed when he heard people’s voices. They made him forget his situation, but he didn’t forbid nurses to do their job.

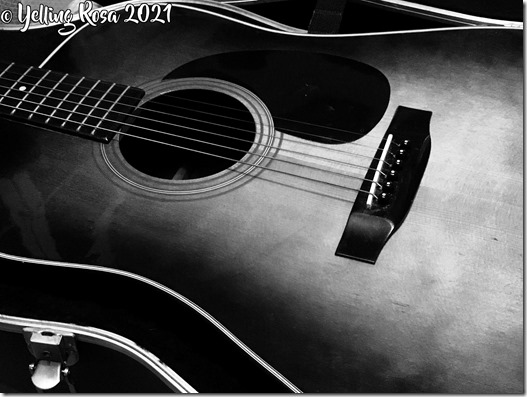

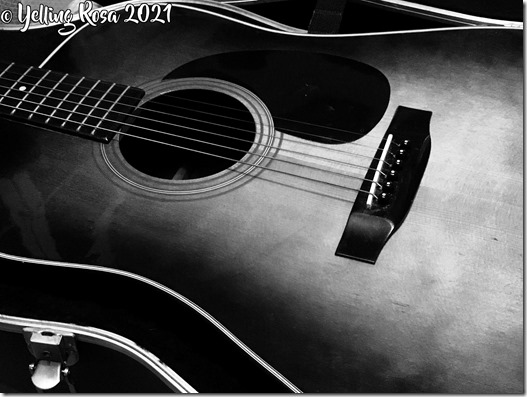

Around nine p.m., some youngsters parked under the window. One of them has a guitar, and he or she played it well. Again one of the nurses ran to the window to make people away. Then the older man said:

”Let them be there. Youngster’s talk makes me feel happy.”

The nurse was uncertain. The patient’s wish was odd, and she was afraid of getting reproaches from the chief nurse if she is let people make noises outdoors. She went out of the room to consult her boss. She was surprised when Mrs. Clayton said: ”You can fulfill the man’s wish because he is alone in the room, and upstairs is also empty.”

When she got back to the patient room, the youngster has become louder, but Mr. Smith was smiling. The nurse, Mrs. Kind, informed his patient what Clayton told her. The evening went on, and the youngsters were singing now—some reason they like to sing old folk songs from the sixties. When the nurse Kind came to see him at ten o’clock, he asked:

”Could you ask them to sing Bob Dylan’s song from the sixties?” She did what the patient asked.

At eleven o’clock, when she came to see Mr. Smith once more, she heard the youngsters were singing ”Blowing in the wind.” The older man has a smiling face and teardrop on his cheek. Mrs. Kind didn’t feel the pulse on her patient’s warm wrist. She walked to the window and said:

”Thank you.”

The young people looked surprised, and the guitar player said:

”Why”?

”Heaven knows,” replied the nurse.

© Yelling Rosa

13/5 –21

PS You can enlarge photo by clicking